The revival of critical mineral extraction and metallurgy threatens French water bodies

Eau Secours 34, 25 April 2024

Key events in the revival of mining and metallurgy in France

Between 1980 and 2005, France closes almost all its mines and associated metallurgical sites, due to competition from countries with much lower production costs.

In 2008, the price of several metals begins to rise again. These metals are now produced outside the EU by a handful of countries that have a quasi monopoly. The Raw Materials Initiative published by the European Commission sets out the economic and geopolitical risks for Member States and proposes ways of securing supplies of these metals for European industry.

The Fillon government then launches the policy of what would later be called the « renouveau minier français » and in 2011 creates the Committee for Strategic Metals (COMES). In 2012, Arnaud Montebourg, Minister for Productive Recovery in the Ayraud government, declares that he wants to make France a mining country again. A simplification of procedures is introduced into the mining code in 2014. In 2015, Emmanuel Macron, Minister for the Economy, Industry and Digital Technologies in the Valls government, launches the « mine responsable » Initiative, which is criticised by all the environmental ngos. In 2016, like Arnaud Montebourg, he advocates the return of mining to France. From 2012 to 2016, a large number of mining exploration and research permits (PERM) are granted, but these are so strongly opposed by local elected representatives, affected communities and environmental ngos that most of them are withdrawn in 2017. This marks the end of the « renouveau minier français », but not the end of the revival of the extraction of critical and strategic minerals in France.

In 2015, the EU launches the EIT RawMaterials within the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT), bringing together manufacturers, research institutes and investors in the field of minerals and metals. At the same time, the EU invests €1 billion in research and innovation between 2014 and 2020. The Horizon Europe programme renews the operation for the period 2021 to 2027. French manufacturers and research institutes benefit from this financial windfall.

In 2021, the « Bureau de recherche géologique et minière » (BRGM), the public entity tasked by the French government with managing underground resources (minerals and water), publishes an Atlas of critical and strategic minerals in the underground of mainland France. The deposits of 24 minerals are located and quantified. It shows that lithium, tungsten and, to a lesser extent, gold have the most easily exploitable deposits. These deposits are mainly in the Armorican massif and the Massif Central, but also partly in the Pyrenees and Alsace. For gold, however, BRGM recommends that priority should be given to exploiting deposits in French Guyana once the problem of illegal gold panning has been resolved. The same applies to nickel, where it recommends exploiting only deposits in New Caledonia.

The long-awaited reform of the mining code begins in 2022 with the adoption of 5 ordinances and a decree. The date of entry into force of some of the provisions of the 2022 ordinances is pushed back to July 2024, demonstrating that the alignment of the Mining Code with the Environmental Code is still giving rise to reservations on the part of the mining and metallurgy industries. The reform continues in 2023 with the adoption of 2 decrees, and several decrees are expected in 2024.

In February 2023, the CNRS and BRGM launch a research programme for the responsible and sustainable use and exploitation of the underground, entitled « Sous-sol, bien commun ». Thanks to new technologies, this programme will make it possible to locate and quantify deposits at a greater depth than the Atlas, and will involve 29 minerals, 5 more than the Atlas.

In March 2023, the European Commission proposes to the European Parliament and the Council a Regulation aimed at guaranteeing a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials. This primarily concerns minerals considered critical and strategic for the energy transition and digital sovereignty. The proposed regulation calls for 10% of the minerals consumed to be extracted from Europe's underground by 2030, and for 40% to be processed in Europe.

On 11 May 2023, the government launches an investment fund dedicated to critical minerals and metals to secure supplies for French industry. The fund, operated by InfraVia, is intended to be invested by the private sector, but the government will provide a further 500 million euros.

On 12 April 2024, the ministers for the economy and energy propose to speed up and simplify the procedures for granting a PERM, which would be reduced from 18 to 6 months, and to include this proposal in the reform of the mining code.

Regulation of mining and metallurgical activities in France

In France, the underground belongs to the owner (public or private) of the land. But the land owners cannot dispose of the underground's resources (minerals, water) as they want, because they are the property of the State (the accepted term is « patrimoine de la nation »). As a result, a mining company must follow a number of procedures set out in the Mining Code in order to obtain a mining permit (PERM or exploitation concession), as well as any renewals or extensions.

The latest reform of the Mining Code describes these procedures in detail. The mining company must submit an environmental, economic and social analysis with its application. This analysis is submitted to the local authorities and concerned communities for their opinion. A public consultation or enquiry must also be held. The application is rejected if one of the competent authorities expresses serious doubts about the possibility of exploring for or exploiting the type of deposit in question without seriously affecting the interests listed in article L.161-1 of the Environmental Code. During the period of validity of a PERM, its holder alone may submit, without competition, an application for a concession for the minerals mentioned in the permit, within the perimeter of the permit.

The latest reform of the Mining Code also specifies who is liable for health and environmental damage caused by exploration or exploitation activities. Liability is not limited either to the perimeter of the mining permit or to its period of validity. In the event of the failure or disappearance of the responsible company, the State is responsible for repairing the damage caused by these mining activities.

Since the « post-mining » has been highly problematic in the past (see paragraph below), the latest reform of the Mining Code requires the company holding a mining permit to declare its work and to make known the measures it plans to take to put an end to nuisances of any kind caused by its activities, and to prevent the risks of such nuisances occurring. The declaration of works is subject to the opinion of the mine site monitoring commission and the concerned local authority, and to public consultation. The mining company is required to apply the prescribed measures as soon as mining activity ceases, for a period of 30 years. The State may also require the parent company to assume responsibility for these measures and liability for mining damage in the event of fraudulent bankruptcy of the subsidiary.

« Post-mining » before the latest reform of the Mining Code

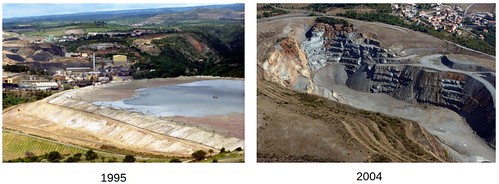

Salsigne in the Aude department is the most polluted mining site in France. It is just one example of a botched « post-mining » that absolves the mining company of its responsibilities.

Salsigne was France's leading gold mine and the world's leading arsenic mine for over a century, until it was shut down in 2004.

The mine has been operated successively by several public and private companies. SMPCS, which was founded in 1924, is bought out in 1980 by Coframines, a public company combining the mining activities of BRGM. Coframines goes into receivership in 1992 and is taken over by LaSource Compagnie Minière, 60% owned by Société Minière Australienne Normandy, Australia's leading gold producer, and 40% by BRGM. The mining, metallurgy and waste storage and treatment activities are then entrusted to 3 LaSource subsidiaries: Mine d'or de Salsigne (MOS), SEPS and SNC Lastours. SEPS goes into receivership in 1996. SNC Lastours ceases operations in 1997 and sells its land to MOS. In 2001, the French government and MOS sign an agreement exempting MOS from the cost of rehabilitating the site. In 2004, MOS ceases mining operations and the French government purchases the land from MOS.

Rehabilitation of the site begins as soon as mining and metallurgical activities cease. It is financed by the State and carried out by the French Environment and Energy Management Agency (ADEME) and BRGM. The securing of the 5 mining waste deposits containing arsenic and sulphur does not, however, prevent record arsenic pollution of the Orbiel river and its tributaries in 2013 (4469 µg/L) and 2018 through rainwater run-off.

Since 1997, the Prefect issues the same order every year: don't eat vegetables grown in areas where the soil and water are potentially contaminated with arsenic, don't use rainwater or river water to irrigate your garden, don't swim in the river, don't eat fish caught in the river...

Since then, several associations (Gratte-papiers, Riverains de Salsigne, Terres d'Orbiel) continue to question the State services, the Regional Health Agency (ARS) and BRGM about the lack of transparency in health monitoring and shortcomings in the rehabilitation of the site. To no avail. The State services play down the health problem and there is no funding earmarked for additional remediation work on the site.

Let's be clear: rehabilitation never returns sites to their original environmental state. But the latest reform of the mining code should, in theory, lead to much better rehabilitation than previously. Above all, it will be more difficult for mining and metallurgical companies to shirk their responsibilities and find excuses not to finance rehabilitation. However, let's not underestimate the ability of these companies to « privatise profits and nationalise losses » and to put pressure on the State, in particular by blackmailing it over jobs.

The threat of water pollution from lithium projects

Lithium is used in the manufacture of lithium-ion batteries for electric cars, a rapidly expanding global market. Lithium is abundant underground, including in Europe. But a few multinationals, notably Chinese, control its production. In order to secure its supply of lithium-ion batteries at a competitive price, the European automotive industry is continually putting pressure on the EU to revive lithium mining and metallurgy in Europe.

There are 3 sources of lithium production: brine from salt lakes called « salars », lithiniferous rock, and geothermal water. Whatever the source, lithium production consumes water and pollutes it. The impact on water is greatest for « salars » and lowest for geothermal water.

In red, the stages of the industrial process that consume and/or pollute water

The 2 most advanced lithium mining and metallurgy projects in France are based on lithiniferous rock and geothermal water respectively.

The EMILI project at Beauvoir, on the site of a former kaolin mine in the Allier department, is being developed by Imerys, a French company that calls itself the « World Leader in Specialty Minerals for Industry », is listed on Euronext Paris and operates in 39 countries.

The Beauvoir mine site adjoining the Colettes forest, a Natura 2000 site

A PERM is granted to Imerys in 2021 until 2025. Following drilling from 2021 to 2023, Imerys estimates the deposit at 116.7 million tonnes, with an average lithium oxide (Li2O) content of 0.90%, and estimates lithium production at 34,000 tonnes per year for at least 25 years.

The exploratory phase is continuing with the opening of a mining exploration gallery (Beauvoir site) and pilot concentration units (Beauvoir site), changeover units (Fontchambert site) and conversion units (Loue site in Montluçon).

On 11 March 2024, the National Commission for Public Debate (CNDP) launches a public debate that will end on 7 July 2024. This will be an opportunity for the Stopmines03 collective and the « Préservons la forêt des Colettes » association to express their opposition to the project and to denounce the « greenwashing » operation on the part of Imerys, whose dossier submitted to the public debate contains many grey areas.

Water consumption for the entire project is estimated at 1.2 million m³ per year, i.e. 600,000 m³/year for concentration and transport, and 600,000 m³/year for conversion. Concentration and transport would use 95% recycled water, thus avoiding any discharge into the environment, but 70 m³/h would be taken from the Sioule river to compensate for evaporation losses. The conversion would use water from the Montluçon wastewater treatment plant at a rate of 75 m³/h; this water would undergo additional treatment to achieve the quality required by the metallurgical process, and reagents (not specified by Imerys) would then be added to it; the effluents generated by the conversion would be treated in such a way as to reuse as much water as possible and thus avoid discharging them into the Cher river; Imerys asserts, but does not explain how, the solid residues resulting from the treatment of the effluents will be eliminated without any impact on the environment. Finally, on the basis of a hydrogeological study it has just carried out, Imérys claims that the drainage of groundwater by the future underground lithium mine will be negligible compared with that of the former surface kaolin mine, which polluted surface water and numerous springs in the area. It goes without saying that all this is contested by the ngos, which deplore the lack of tangible proof of minimal impact on water and the environment, and a discourse whose sole aim is to obtain social acceptance of the project by the local population (promise of jobs and no deterioration or even improvement in the quality of life).

The total investment costs will only be known once feasibility studies have been carried out between 2024 and 2026. But Imerys has already announced a cost of more than €1 billion just for building the underground mine and the lithium concentration, changing and conversion units. The production and « post mining » costs are not estimated in the public debate dossier. In any case, Imerys is not in a position to finance all these costs from its own resources. Imerys has a number of non-exclusive options open to it: forging partnerships with financial investors such as the InfraVia investment fund, and with manufacturers in the mining and metallurgy sectors or electric car manufacturers such as Stellantis (which groups together several French and Italian car brands); taking on debt in the hope that France or other European countries will cover part of the risk associated with the debt.

Lithium de France is awarded another lithium PERM in 2022, but using geothermal water in northern Alsace. Lithium de France is a subsidiary of the French company Arverne, which was set up in 2018 and specialises in the production of low-carbon lithium and geothermal heat.

The 5-year PERM covers an area of 150 km² above the Rhine water table. According to Lithium de France, the geothermal water in the Rhine ditch has a sufficiently high lithium content to make it exploitable. Between now and mid-2024, Lithium de France must locate the most interesting drilling sites to bring up the water, in order to recover both the heat and the lithium.

In September 2023, Arverne is floated on Euronext Paris. Renault Group invests €25.8m in Arverne and signs a supply contract with Lithium de France.

Lithium de France is awarded 3 other geothermal lithium PERMs since 2022, also in northern Alsace, the last of which, « Les Poteries Minérales », in February 2024.

The main risk associated with these PERMs is seismic, as the boreholes will be 2400 m deep. At each extraction site, one well will be used to bring up the water and another to reinject it after extracting the lithium chloride. According to Lithium de France, the extraction of LiCl from the geothermal water will be carried out using a sponge/resin and will not consume or pollute the water. The final stage in lithium purification involves transforming the LiCl into Li2CO3 and LiOH, which are incorporated into lithium-ion batteries. This last stage consumes reagents and water. Lithium de France provides no information on the nature of the reagents used and the fate of the effluents.

Lithium projects based on lithiniferous rock or geothermal water have proliferated in France in recent years.

Most of them are meeting with strong opposition from local populations and sometimes even from their elected representatives. This is the case with Sudmines' application for a PERM (lithiniferous rock in Puy-de-Dôme department) in 2023, and the award of the Ageli PERM (geothermal waters in Alsace) to Eramet in 2021.

The threat of water pollution from tungsten projects

Tungsten is used in the manufacture of alloys, special steels and various components for electrical and electronic applications in a wide range of industries, including aerospace. It is considered a critical and strategic metal because it is produced in small quantities in a small number of countries, including China (84% of world production in 2020).

France was a major producer of tungsten until 1986, when the Salau mining site in Ariège was closed. Between 1971 and 1986, this site produced 14,350 tonnes of tungsten trioxide, which still represents around half of total French production.

The Salau mining site consists of a six-level underground mine on the eastern flank of the Pic de la Fourque, an open-cast mine and an underground mineral processing plant.

Former Salau open-cast mine @ SystExt

The first rehabilitation works were carried out in 1986-1987 and continued between 1996 and 1999. This work focused mainly on the 6 mine waste rock dumps and 2 tailing slag heaps in the Cougnets stream catchment area, representing a total volume of waste estimated at 800,000 m³.

Mine waste rock dump in 2021 @ SystExt

In 2014, Variscan Mines, a subsidiary of an Australian company founded in 2010 by 2 former BRGM executives, applies for a PERM for tungsten on the former Salau mining site. The « Couflens PERM » is granted to Variscan Mines in October 2016.

As the SystExt association explains so well, the award of this PERM triggered awareness among the valley's inhabitants of the health and environmental impacts of the former mining site and of the potential risks of mining being relaunched on the same site.

The mining waste stored on the steep slopes of the Cougnets valley contains high concentrations of metals and metalloids, particularly arsenic and tungsten. The area is regularly subject to heavy rainfall, which causes acid mine drainage. The settling basins at the foot of the 2 slag heaps, which are partially full, no longer perform their settling-filtration role, and their retaining mechanism can break at any time, causing pollution of the Cougnets torrent. A dam has been built downstream of the dumps and spoil heaps to prevent flooding from overflowing the watercourse. The dam receives solid and liquid pollution from the deposits and slag heaps; the accumulation of sediment gradually causes it to lose its water storage capacity. As the dam cannot be cleaned, it can no longer properly fulfil its role as a flood deflector and protection against flooding.

On the strength of these findings, the Stop Mine Salau collective lodged an appeal with the Toulouse Administrative Court against the Couflens PERM, arguing that Variscan Mines' financial package did not allow the project to proceed. As a result, the Toulouse Administrative Court annulled the PERM in 2019, a decision upheld by the Bordeaux Court of Appeal. In 2022, the State Council, to which the French government had appealed, overturned the 2020 decision. A new appeal was lodged, this time denouncing Variscan Mines' failure to carry out an environmental assessment, and the Bordeaux Court of Appeal again annulled the PERM in January 2024. This decision is expected to be final, although Variscan Mines is seeking damages from the State.

As with lithium projects, tungsten projects meet with strong local opposition. For example, the PERM application by Tungstène du Narbonnais in the municipality of Fontrieu in the Tarn department is rejected in 2022 by the Ministry of the Economy and Industry, on the grounds that the mining company had not provided any guarantees regarding the protection of water resources, in particular the drinking water supply for the municipality of Fontrieu. This decision is welcomed by the Stop Mine 81 association, Fontrieu town council and the Haut Languedoc Regional Nature Park, which are opposing mining exploration on the site chosen by Tungstène du Narbonnais since 2018.

Inconsistencies in the policies of the European Union and France

The revival of the extraction of critical and strategic minerals and their metallurgy reveals, if proof were needed, the inconsistencies between energy, climate, environment and water policies at European and French level.

The energy transition will lead to an explosion in demand for critical and strategic minerals, and to meet this demand, we need to revive the extraction of these minerals and their metallurgy. However, as the examples above show, this revival produces waste that will pollute the environment and water bodies for a long time to come. Under these conditions, how can we successfully complete both the energy transition and the return to good quantitative and qualitative status of water bodies by applying the Water Framework Directive?

The dilemma is exacerbated in France, given the importance of nuclear power in the energy mix and the impossibility of guaranteeing the safe storage of nuclear waste over several centuries (see the struggles against the Cigeo nuclear waste burial project).